Health Studies 301 Complementary and Alternative Therapies

Study Guide: Unit 9

Naturopathy

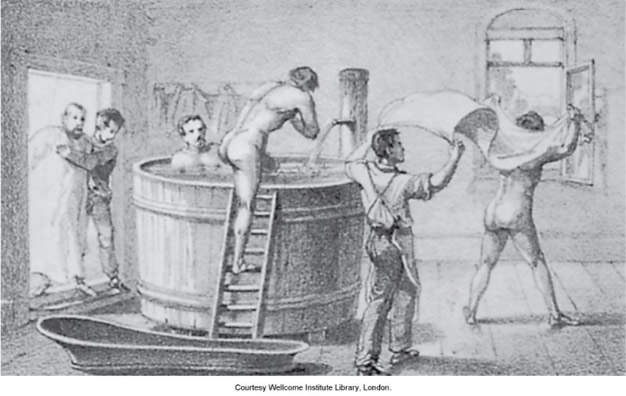

Curative baths, one form of hydrotherapy, were a popular form of natural healing in the late nineteenth century. Wellcome Institute Library via Elsevier Evolve Resources for Micozzi, M. (2015). Fundamentals of Complementary and Alternative Medicine.

Naturopathic medicine is based on the principle that the human body strives toward health and is its own best healer. It embraces the concept of prevention rather than focusing on attempting to seek cures. Naturopath physicians see their role as educators. They treat the whole person and believe that disease prevention is best accomplished through a healthy lifestyle. In that respect, naturopathy resembles health promotion. Naturopathy is the medicine of natural therapeutics and natural cures, or at least that is what it claims to be.

There is a solid rationale for these claims, as shown by the following examples:

- Lung disease caused by smoking is preventable by not smoking and is often reversible, at least to some degree, when a person quits smoking.

- A generally healthy lifestyle is now recognized as the ideal way to prevent coronary heart disease, type 2 diabetes, and hypertension, and is also an effective therapy for these conditions.

Naturopaths consider all diseases are within the scope of their practice and that they can resolve any condition except those that require treatment by medical or surgical intervention, severe trauma, or those that have advanced too far and thereby make naturopathic treatments ineffective.

Learning Objectives

Upon completion of Unit 9, you should be able to

- define naturopathy and articulate the concepts of this therapy.

- describe the types of treatment commonly used by naturopaths.

- identify situations where naturopathy is commonly used.

- determine the effectiveness of naturopathy by analyzing the available research.

Learning Activities

Study Questions

As you complete the activities for Unit 9, keep the following questions in mind. You may want to use the Personal Learning Space wiki on the course home page, and answer these questions as a way of keeping notes to focus your learning.

- What clearly defines the difference between naturopathic doctors and other health care practitioners?

- What parallels can be seen between naturopathic medicine and preventative medicine?

- What does the research say about the effectiveness of naturopathic medicine?

Unit 9 Discussion Forum

When you have completed the other activities for this unit, answer at least one of the questions in the Unit 9 Discussion Forum and respond to at least one posting by a fellow learner.

The more questions you answer, the better prepared you will be for the final exam!

Read

In addition to the notes provided here, read in the textbook:

Micozzi, M. (2019). Fundamentals of Complementary, Alternative, and Integrative Medicine. Pages 279–300.

Naturopathy: The Road to Today

The textbook reading provides an informative history of naturopathy in the United States. It also describes the evolution of the various concepts that are an integral part of naturopathy. The section headed “Therapeutic Influences” (pages 298–300) looks at several areas where scientific advances have taken place in recent decades and that have merged into the philosophy and practice of naturopathy.

Box 22.1 on page 303 makes especially interesting reading. This was written in 1918 when medicine had very few effective treatments. Insulin and antibiotics, for example, had not yet been discovered. The following statement is noteworthy: “The natural system for curing disease is based on . . . the employment of various forces to eliminate the poisonous products in the system.” Despite an almost total absence of supporting evidence, various treatments in popular use today are based on the concept that toxicity is a major cause of disease and that health is improved by the removal of toxins from the body.

Fasting is practised by many people in the belief that it somehow cleans the body. Health food stores sell herbal products that are claimed to bring about “detoxification.” A variation of this concept that toxins are a major cause of disease is described in the section headed “Autotoxicity and Autointoxication” (page 289). Here the focus is on the colon. Several alternative cancer therapies employ enemas, supposedly to clean toxins from the colon. Colonic irrigation is a variation of this for the general population.

Another piece of baggage that naturopathy carries concerns its attitude to infectious disease. For many years, naturopaths have advocated that the true cause of infectious disease is an unhealthy body (see the paragraph starting “Martin Luther Holbrook,” right-hand column, page 287). They often argued that a healthy body, free of toxins, has total resistance to infections. Going one step further, there was opposition in some quarters to immunization. While the concept is a wild exaggeration, it does contain some degree of truth: it is now firmly established that people suffering from malnutrition typically have a weakened immune system and are especially vulnerable to infections.

A recent study carried out on men in Finland reported a strong inverse association between use of a sauna and risk of cardiovascular disease and of all-cause mortality (Laukkanen, Khan, Zaccardi, & Laukkanen, 2015). This suggests that saunas have a strong disease-preventing impact. However, little is known regarding the mechanism by which saunas achieve this (assuming that the effect is real). Any benefit from regular use of a sauna may not apply to other types of hydrotherapy. This is because, first, saunas are often used several times a week and, second, they subject users to a high temperature and therefore much sweating. For these reasons, spending a few days at a spa may not bring about significant health benefits.

The account of the history of naturopathy shows the strong emphasis that was placed on hydrotherapy for many years. This treatment was very popular in central Europe, where people would go to a spa and sit in a pool containing spring water that was credited with healing properties. Indeed, this therapy is still popular in parts of Europe and has been imported into the United States. Saunas and hot tubs are simply variations of this therapy. There is very little evidence that hydrotherapy has any direct therapeutic benefit on body function. But what it certainly does do is induce relaxation. When combined with a few days in a relaxing spa or sanatorium, it is easy to see the attraction of hydrotherapy.

Learning Activity

Read

Micozzi, M. (2019). Fundamentals of Complementary, Alternative, and Integrative Medicine. (Pages 302–307 to “Diagnosis”)

Guiding Principles of Naturopathy

The textbook reading explains the key principles that form the basis of naturopathic medicine. How well do they stand up to close examination?

Naturopaths claim that they treat the whole person (section headed “Treat the Whole Person (Holism)” on page 304). They claim that their approach is altogether different from conventional medicine, which takes a mechanistic view of disease (reductionism) and focuses merely on the symptoms. With some diseases, a whole-person, or holistic, approach can make good sense (in addition to treatments that target the specific problem). For example, coronary disease is the result of a generally unhealthy lifestyle that causes dysfunction in several body systems. For that reason, therapy should emphasize a generally healthy lifestyle. Similarly, a patient with cancer needs nutritional support to help the body recover as well as social and emotional support.

But what about arthritis and depression? With these disorders, there is usually a very specific dysfunction in a single body system. Conventional medicine has treatments of proven effectiveness that target the problem—pain killers for the former, antidepressants for the latter. In these cases, treating the whole body is unlikely to be of much help.

One of the core principles of naturopathic medicine is to use treatments that minimize risk to the patient (section headed “First Do No Harm” on page 304). One can hardly disagree with this rule. But the implication is that conventional physicians do not follow that rule. There is no doubt that many physicians do indeed give inappropriate treatments that cause harm. This is a common problem with prescribed drugs. The obvious solution is to improve the quality of treatment given by conventional physicians. But—more importantly—harmful side effects are often the price patients must pay in order to receive benefit. An obvious example is cancer therapy: drugs, surgery, and radiation all have harmful side effects.

Point 2 of the same section (“First Do No Harm”, page 304) states that naturopaths follow this rule: “When possible, the suppression of symptoms is avoided because suppression generally interferes with the healing process.” This implies that naturopaths would refuse to give pain killers to a patient with arthritis or antidepressants to one with depression. This approach means that patients are deliberately deprived of helpful treatments. Moreover, there is no evidence that these drugs interfere with the self-healing in the joints of patients with arthritis or somehow impede the brain from normalizing its neurochemical imbalances that are the underlying cause of depression.

A point stressed several times in the chapter is that a central tenet of naturopathy is prevention (see section headed “Prevention” on page 305). Over the course of the last several decades, conventional medicine has given more and more attention to this crucial area. For example, conventional physicians routinely screen middle-aged patients for such conditions as pre-diabetes, hypertension, and high blood cholesterol. Interventions are then made, where appropriate, to prevent disease. However, what conventional physicians do, more often than not, is write a prescription rather than encourage their patients to follow a healthy lifestyle. We shall return to this topic later.

Learning Activity

Read

Micozzi, M. (2019). Fundamentals of Complementary, Alternative, and Integrative Medicine. Pages 307–312

The Practice of Naturopathy

Naturopathic doctors (NDs) are trained as primary-care physicians in four-year, accredited doctoral-level naturopathic medical schools. There are two such schools in Canada and several in the United States. NDs can be licensed in four Canadian provinces (British Columbia, Manitoba, Ontario, and Saskatchewan) (Fleming & Gutknecht, 2010). Reimbursements for visits to naturopaths are made by some private health insurance companies but not by provincial governments.

In this part of the chapter, we see how the general principles of naturopathy are put into practice. Naturopathy has adopted several different types of therapy, mainly other types of CAM therapies. These include herbalism, homeopathy, acupuncture, hydrotherapy, physical therapy, spinal manipulation, lifestyle counselling, nutrition (including the use of vitamin and mineral supplements), and psychological counselling. As part of their practice, naturopaths carry out patient assessment and diagnosis using standard approaches, including physical examination, lab tests, and clinical assessment.

To critically evaluate naturopathic medicine, we shall make a comparison between it and conventional medicine. As we shall see, there are negatives and positives on both sides.

We will start with the negatives. Several treatments employed by naturopaths do not stand up to close scrutiny.

The textbook advocates botanical medicine (page 309), yet is highly critical of drugs. As noted above, the logic of naturopathy dictates that practitioners should, whenever possible, avoid giving pain killers to a patient with arthritis or antidepressants to one with depression. Botanical medicine—or herbalism, as it is referred to in this course—is the subject of Unit 10. Herbal medicines are merely plant extracts that contain chemicals with drug-like action. Indeed, many of today’s drugs started life in previous centuries as herbal treatments. It appears that naturopaths have little hesitation in employing herbs as treatments but reject the use of pharmacological substances, even if they are substances found naturally in plants that have been made synthetically in a lab!

Homeopathic medicine is uncritically accepted (page 309–310). This therapy is explored in Unit 12. Contrary to what is implied in the textbook, homeopathy is highly controversial and is far from being proven effective. Let us suppose for one moment that homeopathy actually works. In that case its mechanism of action is just like that of herbs and drugs, i.e., it causes beneficial changes in body function. This again poses the question: What is the logic in accepting treatment with some chemicals (such as homeopathic or herbal medicines) but rejecting it for others (pharmaceuticals)?

The textbook states that acupuncture is “effective for management of many diseases” (page 310). As we saw in Unit 7, this assertion is very far from proven.

The textbook states that hydrotherapy is used by naturopaths “to detoxify, and to strengthen immune function” (page 310). As was mentioned earlier, there is scant supporting evidence for this. However, hydrotherapy can be of much value for general relaxation, whether as a 20‑minute session in a sauna or as a one-week stay at a spa.

Detoxification was also discussed earlier. Here again, the textbook is on very shaky ground (page 311). A survey of naturopaths in the United States (Allen, Montalto, Lovejoy, & Weber, 2011) found that

92% of respondents reported using clinical detoxification therapies. Over 75% of respondents utilized detoxification therapies primarily to treat patients for environmental exposures, general cleansing/preventive medicine, gastrointestinal disorders, and autoimmune disease. Regarding methods used, >75% reported using dietary measures, reducing environmental exposures, and using botanicals as detoxification therapies.

Similar findings emerged from a survey of naturopaths in Canada (Verhoef, Boon, & Mutasingwa, 2006). More than half reported using fasting as a treatment. In addition, a small minority use “colon therapy.” This usually refers to the practice of colonic irrigation, a treatment that was mentioned earlier in which the colon is flushed of its contents using an enema. Fasting and colonic irrigation are intended to induce “detoxification,” but neither delivers any proven benefit. Fasting has been identified as detrimental in certain conditions and may even be life threatening. Colonic irrigation has been noted to hyperextend the colon and disrupt the natural process of contraction to expel waste products.

These two surveys reveal that large numbers of naturopaths are carrying out interventions based on two assumptions: 1) that toxins are causing health problems, and 2) that various interventions such as diet, herbs, fasting, and colon irrigation, can somehow “detoxify” the body. There is extremely little published research that in any way supports these claims.

The textbook reading provides three examples of how naturopaths treat patients (pages 311–312). Each treatment plan has at least one serious problem:

- Cervical dysplasia. The standard medical procedure involves minor surgery. This is safe and effective. Instead, the textbook recommends botanical treatment but provides no supporting evidence for its efficacy.

- Migraine headaches. Again, the textbook rejects conventional treatment. Instead, it recommends various nutritional treatments, including a supplement supplying 400 mg of riboflavin per day. This dose is about 300 times higher than the Recommended Dietary Allowance (RDA) for a man. Such a megadose of a vitamin is more akin to drug therapy than to a nutritional therapy. It is hard to see the logic in rejecting a drug that is proven to alleviate symptoms while recommending megadoses of vitamin.

- Hypertension. The textbook recommends several appropriate dietary treatments. However, it then recommends mistletoe, while making no mention of drugs. Several drugs are widely used for hypertension. Diuretics in particular have been much studied and are of proven effectiveness. They are also cheap and safe. By contrast, mistletoe has not been properly tested in clinical trials and is toxic. This really makes no sense!

In addition to the various therapies discussed above, there are several others used by at least some naturopaths. This was documented by the survey of naturopaths in Canada cited above (Verhoef et al., 2006). About 23% use iridology in their practice. This is a form of diagnosis, not therapy. As explained in Unit 17, it has no scientific basis.

We shall now turn to aspects of naturopathic medicine where it compares favourably with conventional medicine. As was stated earlier, naturopathic medicine places a strong emphasis on avoiding treatments that pose a risk to their patients. Unfortunately, what this can often mean is that patients are denied treatments that are effective while posing an acceptably low risk of harm.

Conventional physicians often go too far in the opposite direction. In particular, there have been many stories over the past several decades of medications being prescribed that cause significant harm. A recent example of this concerns the prescribing of OxyContin and other opioids that are widely used for pain relief. There is strong evidence that physicians are guilty of widespread over-prescribing of the drug, and this has caused thousands of patients across North America to become addicted. This has led to thousands of deaths (Dhalla et al., 2009).

Naturopaths place a strong emphasis on preventive medicine by encouraging their patients to live a healthy lifestyle. There is little doubt that, if asked, the great majority of conventional physicians would agree with this approach. And, indeed, they do to some extent practise preventive medicine. For example, patients with diabetes or coronary disease will often be given a referral to a dietitian, who will then give advice on how to eat a healthy diet. Much of our current knowledge on how lifestyle is related to disease comes from clinical studies that have been carried out by conventional physicians. The problem is—and this is a major problem—in their everyday work, conventional physicians give much too little emphasis to lifestyle for both prevention and treatment. Instead, they are more likely to reach for their prescription pad.

Here is one study that demonstrates this problem. The textbook (page 312) refers to the role of diet and lifestyle in relation to hypertension. Many clinical studies have demonstrated the effectiveness of this approach. Yet anyone being treated by their physician for hypertension is unlikely to receive anything other than a prescription for a drug that lowers the blood pressure.

Here is another example. No condition is easier for a physician to diagnose than obesity. Moreover, it cries out for intervention, or at least some encouragement to patients to try to control their weight. Yet a study carried out in Canada reported in 2012 that less than one-third of overweight people had been advised by their physician to lose weight (Kirk, Tytus, Tsuyuki, & Sharma, 2012).

Why do conventional physicians routinely ignore lifestyle when treating their patients? It can hardly be through lack of awareness of the subject, as the information is so well known. The obvious explanation is lack of time. Writing a prescription for drugs that treat hypertension or high blood cholesterol takes a mere few minutes, whereas counselling patients on making lifestyle changes is far more time consuming. In a system where physicians generally spend no more than 10 or 15 minutes on each consultation, it is simply not possible to make a serious effort to assess a patient’s lifestyle and then deliver appropriate counselling. Naturopaths, by contrast, spend much more time with their patients. As the textbook points out (page 376), “A typical first office visit to [a naturopath] takes one hour.”

Summary

Naturopathic medicine offers an approach to health that appeals to many people: it is holistic and preventive, promises treatments that “detoxify” the body, and avoids the potential hazards often seen with conventional medicine.

Naturopathic medicine and conventional medicine have lived poles apart for a century. But in recent decades, the gap has been slowly narrowing. A major reason for this is that discoveries since the 1970s have shown the enormous potential of preventive medicine. In many cases this involves drug therapy. Conventional physicians have no problem using drugs for disease prevention, whereas naturopaths frown on their use. Preventive medicine also includes lifestyle interventions, including diet. Here, naturopaths have no hesitation in recommending these to their patients, while conventional physicians are much less likely to, mainly due to lack of time.

The strong emphasis that naturopaths place on encouraging their patients to prevent disease by living a healthy lifestyle is a strong positive feature. Also, as naturopaths are opposed to the use of treatments that pose a risk, they are unlikely to harm their patients by, for example, causing opiate addiction.

Naturopaths typically employ an assortment of CAM therapies. It requires convoluted logic to justify using such therapies as herbalism, homeopathy, and acupuncture while rejecting drugs that have been shown to be safe and effective. The obvious explanation for this approach to medicine is that naturopaths have deeply held philosophical beliefs that lead them down this road.

While the textbook is generally very negative on the use of drugs, it does contain this statement (page 307):

[T]o fulfil their role as primary care family physicians, NDs may also administer appropriate vaccines and use therapies such as office surgery and prescription drugs when less invasive options have been exhausted or found inappropriate. In the restoration of health, prescription drugs and surgery are a last resort but are used when necessary.

Unfortunately, we have little clear data on how many naturopaths do recommend the use of drugs in their everyday practice.

Learning Activity

Self-test Quiz

Do the self-test quiz for Unit 9 as many times as you wish to check your recall of the unit’s main points. You will get a slightly different version of the quiz each time you try it. (This quiz does not count toward your final grade).

If you have trouble understanding the material, please contact your Academic Expert.

References

Allen, J., Montalto, M., Lovejoy, J., & Weber, W. (2011). Detoxification in naturopathic medicine: A survey. Journal of Alternative and Complementary Medicine, 17(12), 1175–1180. doi: 10.1089/acm.2010.0572.

Dhalla, I.A., Mamdani, M.M., Sivilotti, M.L., Kopp, A., Qureshi, O., & Juurlink, D.N. (2009). Prescribing of opioid analgesics and related mortality before and after the introduction of long-acting oxycodone. Canadian Medical Association Journal, 181(12), 891–896. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.090784.

Fleming, S.A., & Gutknecht, N.C. (2010). Naturopathy and the primary care practice. Primary Care, 37(1), 119–136. doi: 10.1016/j.pop.2009.09.002.

Kirk, S.F., Tytus, R., Tsuyuki, R.T., & Sharma, A.M. (2012). Weight management experiences of overweight and obese Canadian adults: Findings from a national survey. Chronic Diseases and Injuries in Canada, 32(2), 63–69.

Laukkanen, T., Khan, H., Zaccardi, F., & Laukkanen, J.A. (2015). Association between sauna bathing and fatal cardiovascular and all-cause mortality events. JAMA Internal Medicine, 175(4), 542–548. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2014.8187.

Verhoef, M.J., Boon, H.S., & Mutasingwa, D.R. (2006). The scope of naturopathic medicine in Canada: An emerging profession. Social Science & Medicine, 63(2), 409–417. doi:10.1016/j.socscimed.2006.01.008.